Documentation

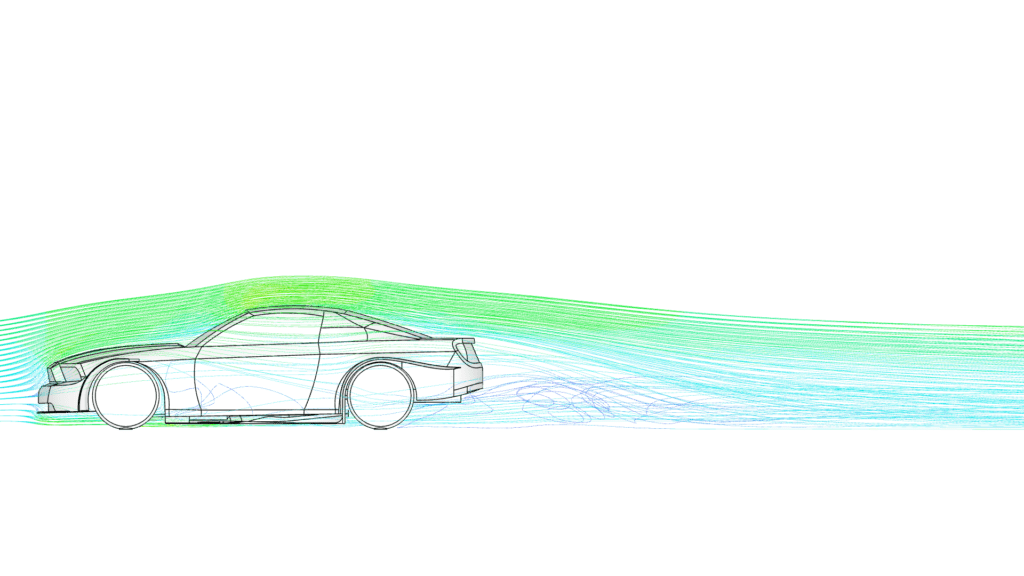

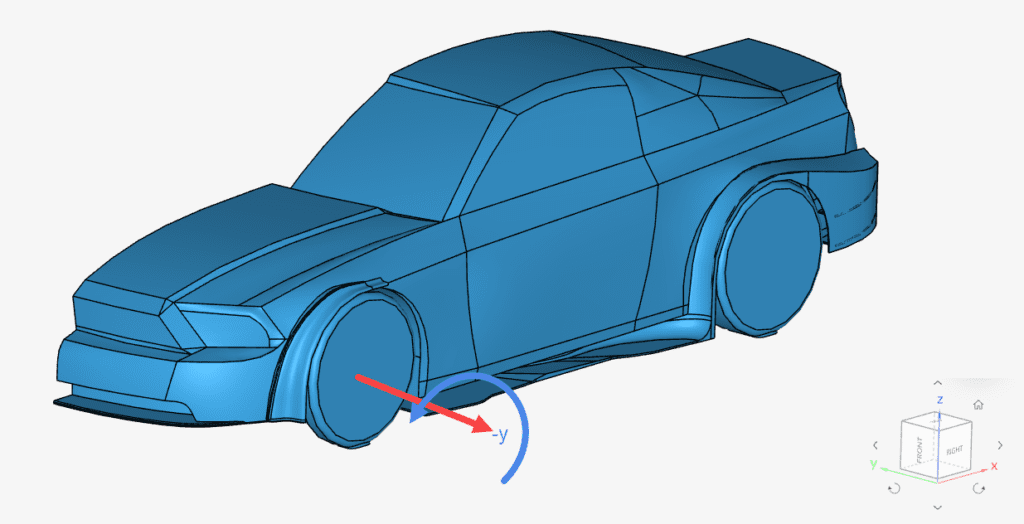

This tutorial shows how the aerodynamics of a vehicle can be analyzed by setting up an incompressible turbulent airflow around a moving vehicle. Figure 1 shows an example of the resulting flow behavior:

This tutorial teaches how to:

We are following the typical SimScale workflow:

The first step is to click on the button below. It will copy the tutorial project containing the geometry into your Workbench.

Figure 2 demonstrates what should be visible after importing the tutorial project:

Note that the car geometry is not too detailed. Small and detailed features that don’t greatly affect aerodynamics, such as bolts and windshield wipers, should be removed or simplified.

With this approach, the computation effort necessary throughout the entire simulation process can be reduced, while still obtaining meaningful results. Find more information about CAD preparation on this documentation page.

Did you know?

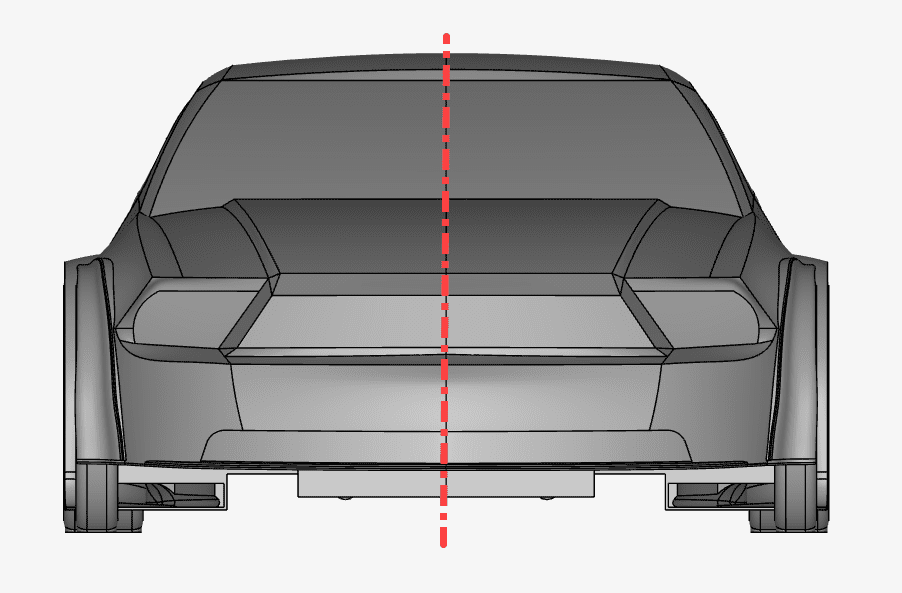

We can use the car’s symmetrical shape in our favor. As we expect the flow field to be mirrored along the symmetry plane of the car, we only need to use one half of the geometry. As a result we reduced the size of the flow region and the simulation will run faster, as only half of the cells are needed.

Crosswind Simulations

Note that the symmetry assumption does apply to analyses where the vehicle is traveling in a straight line with no crosswind. For crosswind analyses or cornering situations where the flow is oblique relative to the vehicle, a full vehicle analysis is required.

The first step for this simulation is the creation of the fluid region. This will be the flow domain that will be used for the external aerodynamic analysis. For the incompressible analysis type, only the fluid region is used. The SimScale ‘Edit in CAD mode’ is used to generate the flow region around the geometry that was imported. Eventually, the geometry of the car will be discarded, so only the flow region remains. To enter the CAD mode click on the following icon:

The External option is used to create the flow region around the model. Select ‘External’ next to Create, at the top left of the interface.

The dimensions of the flow region are chosen according to the length (L) of the vehicle. As a rule of thumb, the following values can be used:

To further simplify the simulation the symmetric shape of the car is used to reduce the size of the flow domain. Set up the flow region dimensions in meters as shown below:

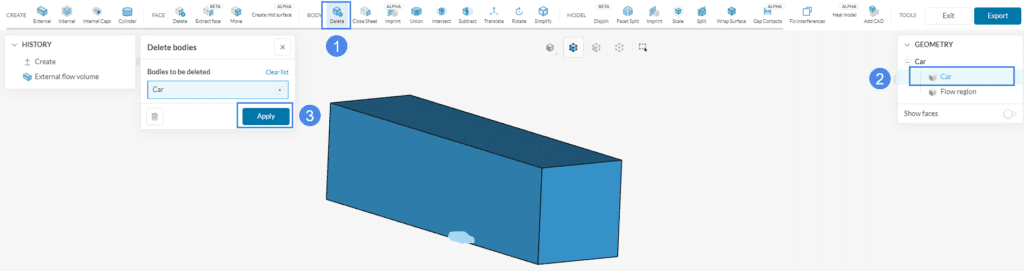

After you are done, click ‘Apply’. Then select the ‘Delete’ feature next to the BODY section, to remove the ‘Car’ solid part:

Select ‘Car’ from the Geometry tree at the top right and click ‘Apply’.

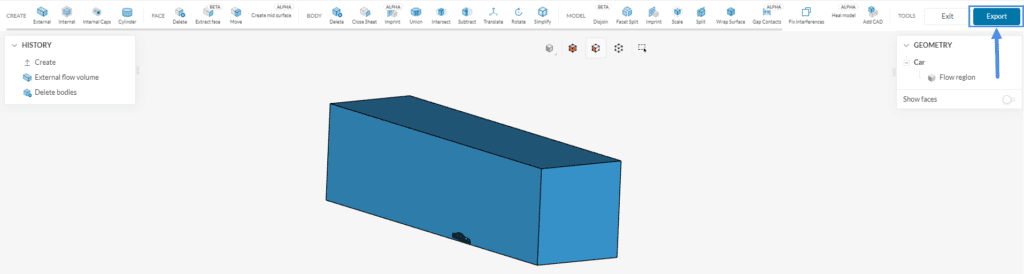

When the operation is finished and the car body is removed successfully, click on ‘Export’ at the top right of the interface to get redirected to the Workbench:

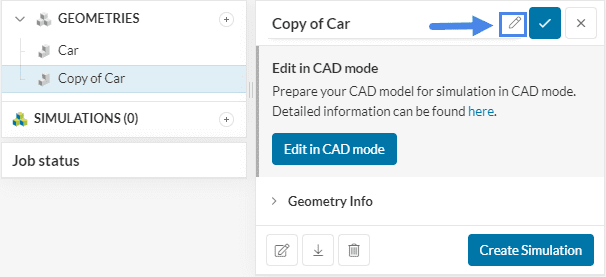

After the export two geometries are now in the geometry section, Car and Copy of Car. For better clarity rename Copy of Car as ‘Car Flow Region’:

To start the simulation setup process, select the CAD ‘Car Flow Region’ and click on the ‘Create Simulation’ button.

Doing so opens the analysis type choice widget. Choose ‘Incompressible’ as the analysis type. It can be used for cases where the Mach number remains lower than 0.3 in the entire domain, which will be the case for this tutorial. Proceed by clicking on the ‘Create Simulation’ button.

The simulation tree will be visible on the left-hand side of the interface. We have to set up all entries to be able to run the simulation. The global settings of the simulation remain as default:

In this tutorial, we want to calculate the steady-state solution, which is independent of time. SimScale also supports transient analysis, which allows the calculation of time-dependent results.

Did you know?

The k-omega SST turbulence model is recommended for external aerodynamics cases.

It works as a blend between the k-omega and k-epsilon models. The k-omega model is predominant in the near-wall, switching to the k-epsilon model in the free-stream.

Find more information about the k-omega SST model in this documentation page.

Saved Selections are groups of faces. They are particularly helpful when the same group of faces is used several times during the simulation setup. The user can quickly select a given group of saved selections at once whenever they need to be assigned to a condition.

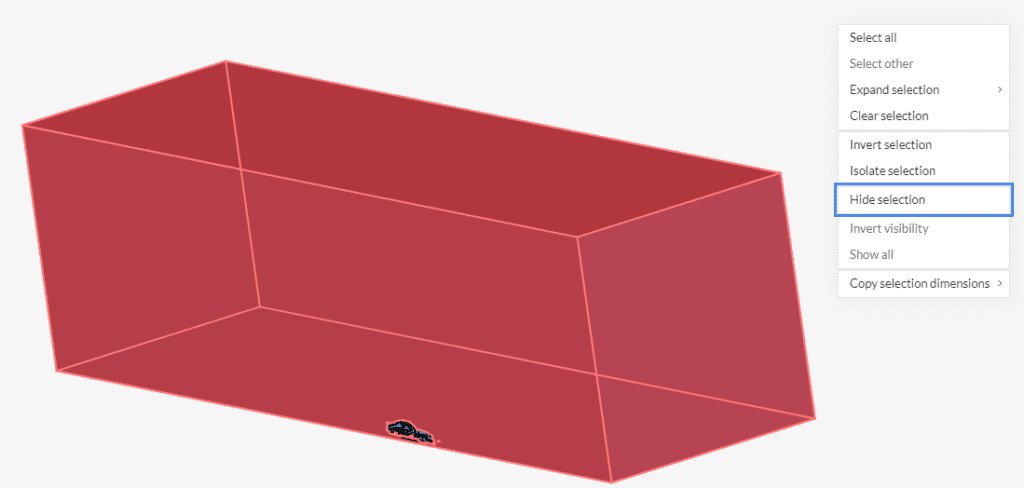

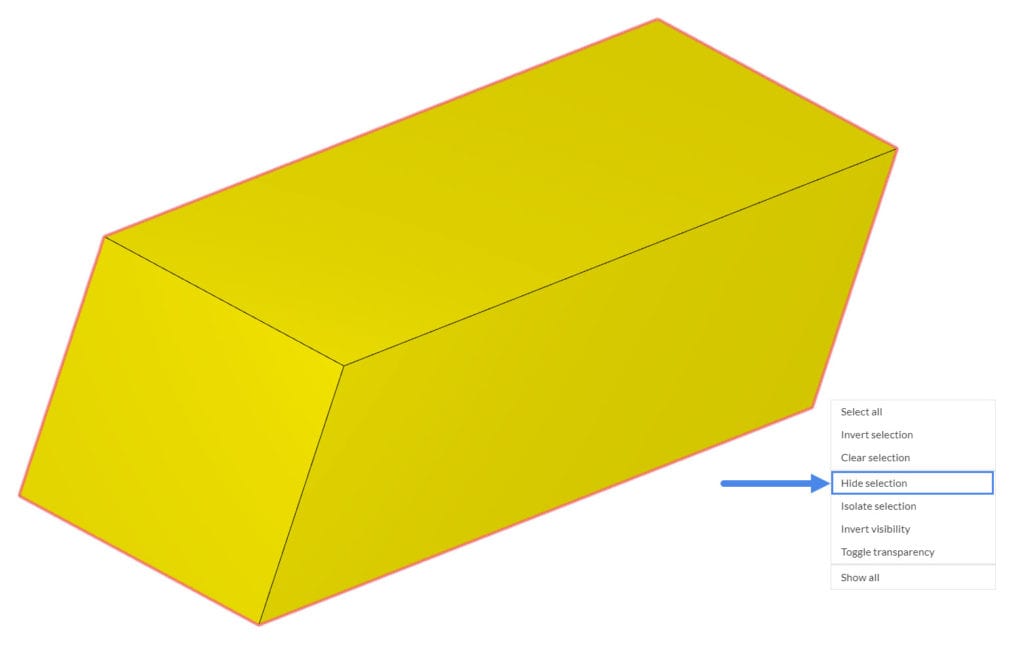

Let’s create three saved selections for this tutorial. To begin with, hide the walls of the flow region. To do this, select all six faces of the domain by rotating the model (they should turn to red). Then right-click in the viewer, and pick the ‘Hide selection‘ option, so they turn invisible.

After the walls of the domain are hidden, follow the steps below:

Now, let’s create one saved selection for the remaining faces of the vehicle. Follow the steps below:

After creating the Body saved selection, you can make the walls reappear by right-clicking in the viewer and selecting ‘Show all’. The walls of the flow region will be necessary to assign boundary conditions later on in the tutorial.

Now we are ready to set up the physics of the simulation.

In the simulation tree, click on the ‘+ button’ next to Materials.

After opening the materials section, select ‘Air’ from the SimScale materials library. Click on ‘Apply’ to confirm your selection.

The flow region that was created at the beginning of the simulation setup is automatically assigned to the material:

Did you know?

For this tutorial, we will use the default values for the air properties. It’s possible, however, to edit each one of the values from Figure 19 by clicking on them.

The physical situation simulated is a car moving with 20 \(m/s\). Now it is rather difficult to directly model the car’s velocity in a CFD simulation. We get the same result if we turn the situation around. Instead of a moving car and the still-standing street, we make the car stand still and let the air around the car and the street move with 20 \(m/s\).

An overview of the boundary conditions for the domain can be seen below:

Similarly, for the car walls, the following boundary conditions are applied:

To create a boundary condition, click on the ‘+ button’ next to Boundary conditions, and select the desired type from the drop-down menu.

a. Velocity Inlet

Let’s define the air velocity at the inlet face. To do so, create a new boundary condition, selecting ‘Velocity Inlet’ from the drop-down menu, as seen in Figure 22.

With a Fixed value velocity inlet boundary condition, the velocity that we define is a vector. You can use the orientation cube in the bottom-right corner of the viewer for reference. In this tutorial, set the velocity in the x-direction to ’20’ \(m/s\). Last assign the front face of the flow region to the boundary condition.

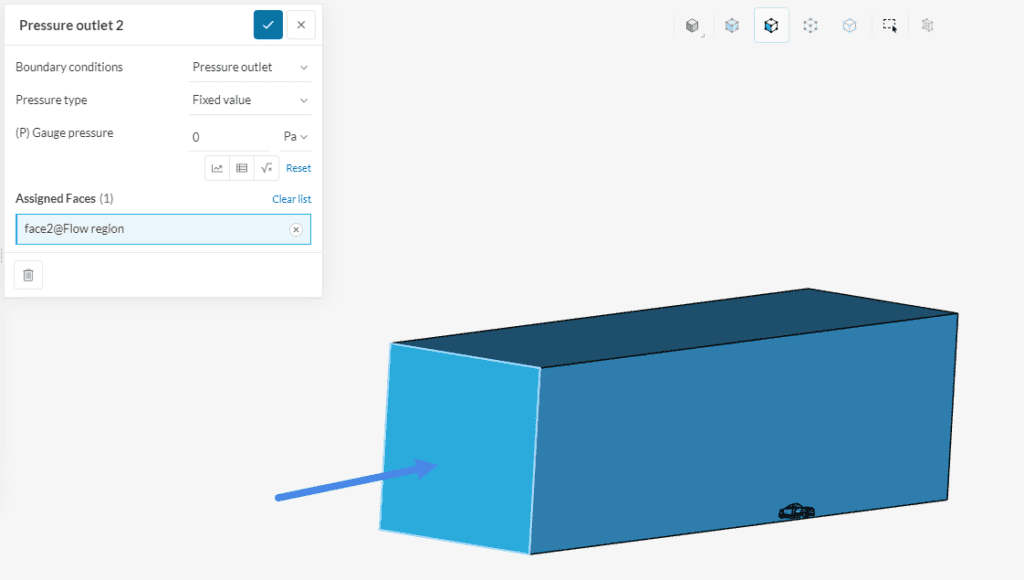

b. Pressure Outlet

We want to specify the outlet of the flow region as normal atmosphere, zero gauge pressure. Create a second boundary condition, this time a ‘Pressure Outlet’ and specify a fixed gauge pressure. The gauge pressure is relative to a reference value (ambient pressure, for example). Therefore, a pressure outlet condition with ‘0’ \(Pa\) gauge pressure is applied to the outlet face of the domain. Assign the back face of the flow region to this boundary condition.

c. Walls: Slip Condition

For the third boundary condition, select ‘Wall’ from the drop-down menu. Set (U) Velocity to ‘Slip’.

The slip condition allows flow tangent to the face without the creation of a boundary layer, but won’t allow flow in a normal direction. This is a good approximation for the top and side faces of the flow region, which are far away from the car. Therefore, assign the slip wall condition to the top (XY-plane) and the right side (XZ-plane) of the domain, as seen below. Assign both, the right and the top face of the flow region to this boundary condition.

d. Symmetry

As previously discussed, a ‘Symmetry’ boundary condition will be applied to the symmetry plane, since we expect mirrored aerodynamic flow patterns on the two sides of the car. Assign the symmetry face to the boundary condition.

e. Wall: Moving Wall

Now, assign a boundary condition to the ground face which is the street. Create another ‘Wall’ boundary condition. For better clarity rename the boundary condition to ‘Street’. This time, set (U) Velocity to ‘Moving wall’. In this configuration, specify the tangential component for the fluid velocity on the assigned face.

Define a velocity of ’20’ \(m/s\) in the x-direction, which is the same vector that was defined for the velocity inlet boundary condition.

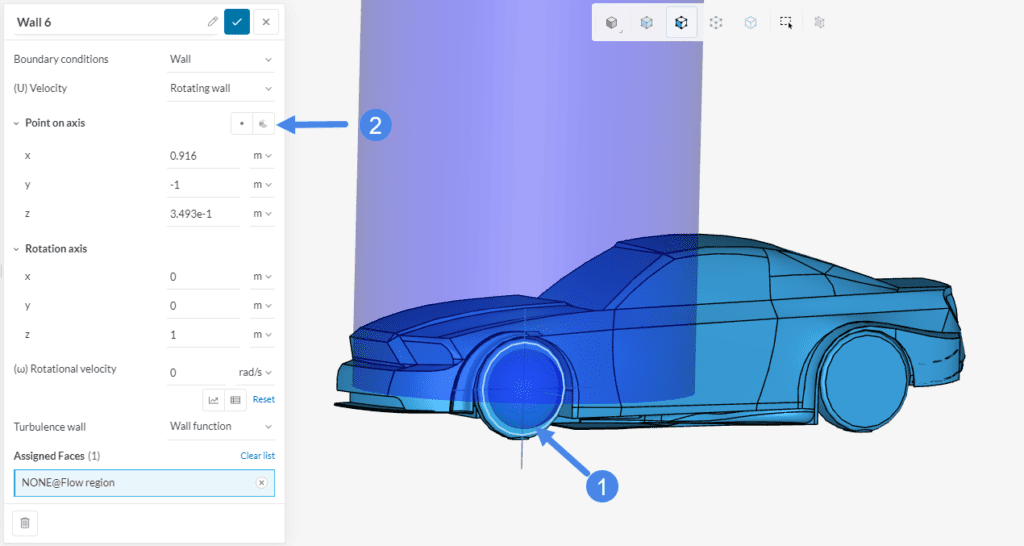

h. Wall: Rotating Wall – Front Wheel

We can model the rotating car wheels with a ‘Wall’ boundary condition. This time, select ‘Rotating wall’ for (U) Velocity. The following information is necessary to set up a rotating wall condition:

$$\omega = \frac {U} {r} \tag{1}$$

Where \(U \ [m/s]\) is the linear velocity of the car and \(r\ [m]\) is the radius of the wheel.

In our case, the car velocity is 20 \(m/s\) and the wheel radius is 0.3495 \(m\). Therefore, our rotational velocity \(\omega\) is ‘57.22’ \(rad/s\).

Now we have the necessary information to set up the rotating wall condition for the front wheel, as seen in Figure 30 below:

Simulating Rims

In this tutorial the rims of the car are simplified with a closed face. This is a simplification to most street vehicles. The rim of a wheel is usually made of spokes, which allows air to pass through the rim. In order to capture the effects of a rotating rim the advanced concept of a rotating zone can be used.

You can learn more about this concept on this documentation page.

g. Wall: Rotating Wall – Rear Wheel

The same procedure is also followed for the rear wheel. The only difference between the front wheel and the rear wheel boundary conditions will be the Point on axis coordinates.

Please set up the final wall boundary condition as shown below:

Automatic boundary condition assignment

For all faces not assigned to a specific boundary condition SimScale will set the boundary to a no-Slip wall condition.

Find in this article relevant information about wall functions and other wall treatments.

In the simulation tree, click on the ‘Simulation control’ tab, and configure it as shown:

Did you know?

In a steady-state simulation, the End time and Delta t parameters control the number of iterations to be performed. With the default settings, a simulation consists of a total of 1000 iterations, which is enough for most simulations to converge.

For more notes on the simulation control settings, please visit the following page: Simulation control for fluid flow simulations.

Lift and drag coefficients are some of the most important parameters when evaluating the performance of the flow aerodynamics of a vehicle. Therefore, let’s create a ‘Force and moment coefficients’ result control, as shown below:

Please set up the result control as below:

Aerodynamic Balance

When setting up the force coefficient report the center of the rear wheel is selected. This setup helps to calculate the aerodynamic balance of the car, Dividing the result of the moment report with the wheelbase the force coefficient of the front axle is calculated. Dividing the force coefficient of the front axle with the total lift coefficient results in the aerodynamic balance in the percentage of the frontal load. $$ \%_{Front} = \frac{Coef.Moment_{Rear}*Reference\ Length}{Wheelbase * Coef. Lift_{Total}} $$

Important

Be careful when setting up the result control parameters, as they are used by the algorithm to calculate the drag and lift coefficients.

For the drag and lift formulas, and more examples on how to set up the forces and moment coefficients result control, please refer to the following articles:

How to analyze the pitch, lift, and drag coefficients?

Why are my lift and drag coefficients too big/small?

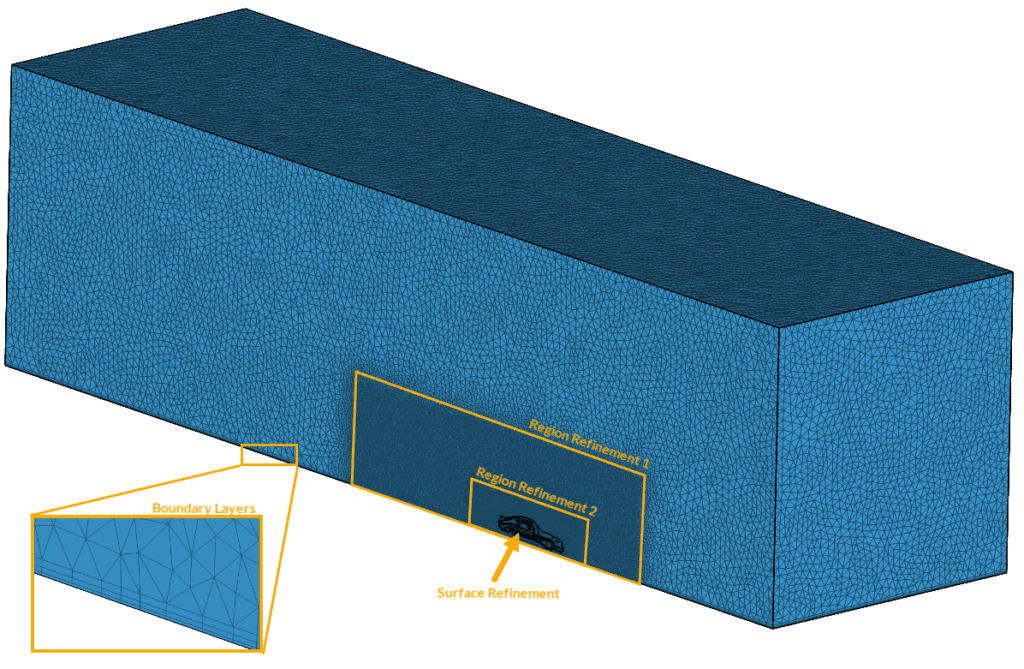

For the meshing operation, we recommend using the standard algorithm. The standard meshing algorithm is a good choice in general, as it is quite automated and delivers good results for most geometries, with the following default properties, including a Small feature suppression of ‘0.001’ \(m\) under the Advanced settings:

Did you know?

Often, large changes in the mesh’s cell sizes only occur in few regions. Increasing the global mesh refinements increases the number of cells drastically.

When using the standard mesher, SimScale offers a physics-based meshing option, which automatically refines the regions around the inlets and outlets.

You can also do this manually, by using one of the local refinement options, foremost being local element size and region refinements.

If you want to learn more about the Standard meshing algorithm, please have a look at the relevant documentation page.

Why do we need mesh refinements?

In external aerodynamic simulations, as air flows around the body, two regions have important physical effects: the regions close to the car body and the wake region, which develops downstream from the object.

Since the gradients in velocity and pressure are large in those areas, they require finer cells to be resolved accurately. Therefore, further refinements will be necessary.

Use region refinements to more accurately capture the wake and the aerodynamic flow around the car. A region refinement is used to refine the volume mesh for one or more user-specified geometry primitives.

To add a refinement region to your mesh, first, create two geometry primitive boxes. On the right-hand panel click the ‘+ button’ next to the geometry primitives and select the cartesian box.

a. Region Refinements

Set the values for the first region refinement as seen below. This region refinement is used for the first refinement region of the far field around the car.

Rename the first box ‘Far Field’ and add the dimensions as follows:

Repeat the process to create the second smaller box. This box is used to even further refine the mesh directly around the car.

Rename the box to ‘Close Field’ and the dimensions of the box are as follows:

Notice how the boxes extend further downstream from the car. The objective is to capture the high gradients from the wake, which is pictured in Figure 37.

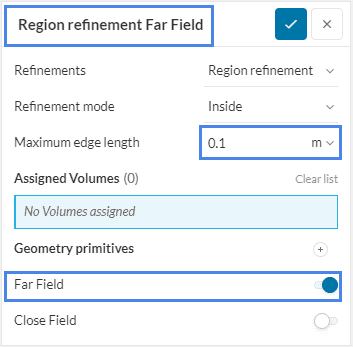

Next, create a new Region refinement by clicking on the ‘+ button’ and selecting ‘Region refinement’.

Rename the region refinement as ‘Region refinement Far Field’ and set the Maximum edge length to ‘0.1’ \(m\) and toggle on the Far Field selection:

Repeat the process for the Close Field. As the smaller box is closer to the surface, a finer discretization will be enforced. Please set the Maximum edge length to ‘0.07’ \(m\):

b. Local Element Size

To refine the cells directly at the wheel faces a local element refinement is used. This refinement is applied to faces and limits the cell edge lengths based on the input.

Create a ‘Local element size Wheels’ refinement and set the Maximum edge length to ‘0.005’ \(m\). Assign it to both ‘Front Wheel’ and ‘Rear Wheel’ saved selections, to capture the region next to the rotating walls accurately.

Now you can go back to the main meshing settings and click on ‘Generate’, as in Figure 36. Note that this is not a mandatory step: You can also just start the aerodynamic flow simulation and the mesh will be created automatically. However, let’s have a look at the finished mesh in this simulation before starting the simulation.

This mesh will take around 30 minutes to complete and this is what it will look like:

Be Aware

This tutorial presents how the simulation is set up for a successful CFD run. The setup for this tutorial is simplified. To ensure the reliability of the results, a series of studies have to be performed.

Further tests with finer meshes, improved layering control, extended flow region, etc., should be performed.

Naturally, it’s important to make sure that each of the simulation runs are also converging. For bigger meshes, it might be necessary to prescribe more iterations.

For more insights on how to assess convergence in a CFD simulation, please refer to this documentation page.

The simulation setup is now ready. We can proceed to create a new simulation run. To do so, click on the ‘+ button’ next to Simulation Runs.

This way, if not generated in advance, the mesh will be generated, and, afterward, the simulation run will start automatically. While the simulation results are being calculated, you can already have a look at the intermediate aerodynamic flow results in the post-processor. They are being updated in real-time!

You will also find a link to the finished project at the end of the tutorial.

Note

A red warning message may appear, stating that the duration of the simulation exceeds the maximum runtime. The defined maximum runtime of 30000 seconds will be enough for this simulation, therefore, please proceed by clicking on ‘Start’:

The simulation run takes about 70 minutes to finish. At this point, you can access the post-processing environment by clicking on ‘Solution Fields’ or ‘Post-process results’:

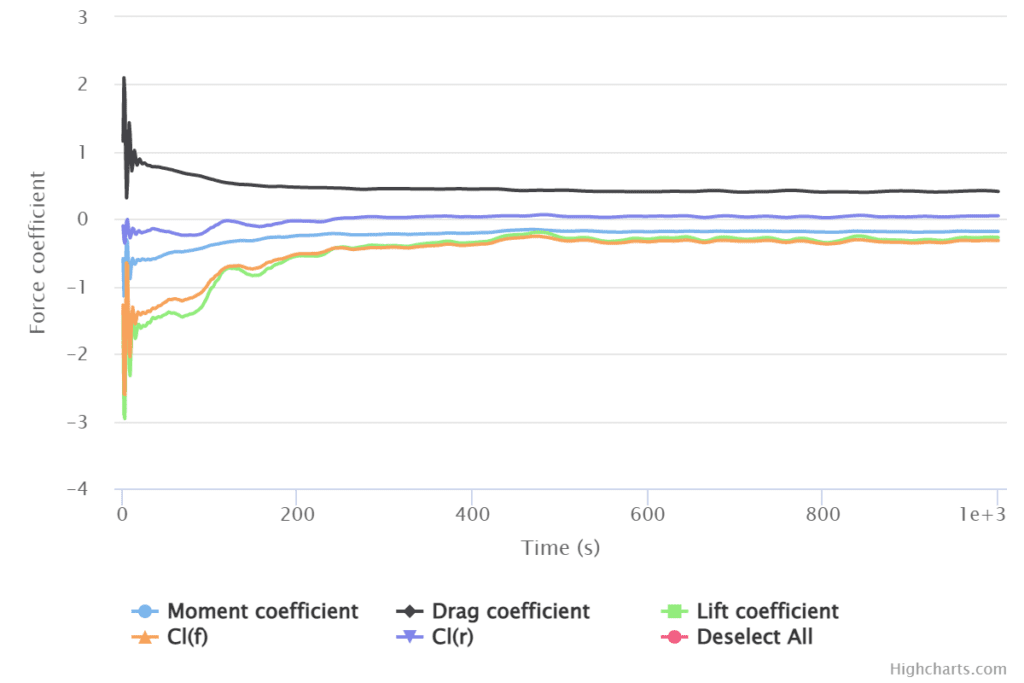

The drag and lift coefficients are available in the ‘Force and moment coefficients’ tab:

The plot shows you how the coefficients are changing throughout the simulation process, as the iterations go on. In a converged simulation, the coefficients will stabilize around a value.

Therefore, in a steady-state simulation, the intermediate results are important to assess convergence. The final, converged solution is the one that should be analyzed to obtain the aerodynamic flow parameters.

Calculating the Aerodynamic Balance

From the force and moment coefficient report it can be seen that a moment coefficient of -0.18 and a lift coefficient of -0.27 is calculated. As the force and moment coefficient report was defined at the center of the rear wheel the aerodynamic balance of the car can be calculated using the formula \(1\) below.

$$\%_{Front} = \frac{Coef.Moment_{Rear}*Reference Length}{Wheelbase *Coef.Lift}\tag{1}$$

The wheelbase of the car is 2.665 \(m\) and the reference length was set to 4.6 \(m\). Using these values an aerodynamic balance of 115% front is calculated. This means that most of the aerodynamic force is on the front axle of the car.

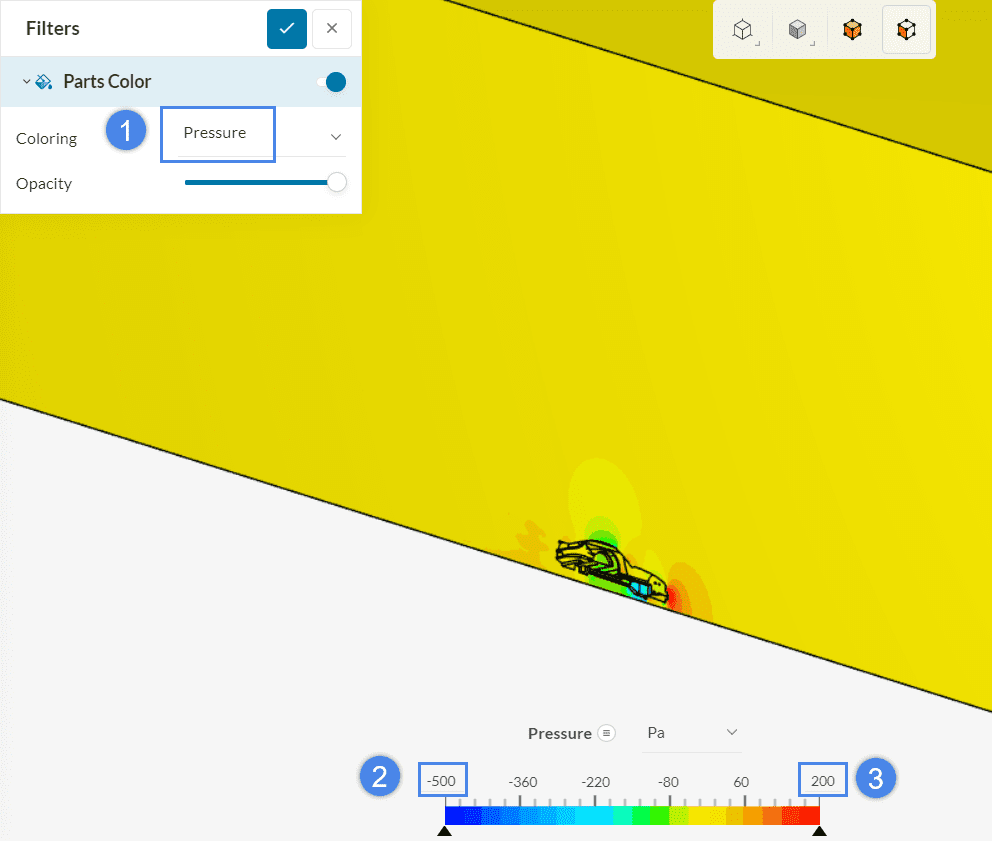

After accessing the post-processor, you can use several post-processing filters to further analyze the results. If the pressure distribution is not yet visualized, go to Parts color and change the Coloring to ‘Pressure’. The legend at the bottom of the page includes a default range set by the lowest and highest values inside the domain. By clicking on the upper and lower limits and editing their values, you can control the quality of visualization, making sure that the color map on the surface is insightful.

To better visualize the aerodynamic flow around the car you can hide the flow region by selecting all faces of the flow region, right-clicking your mouse, and choosing ‘Hide selection’.

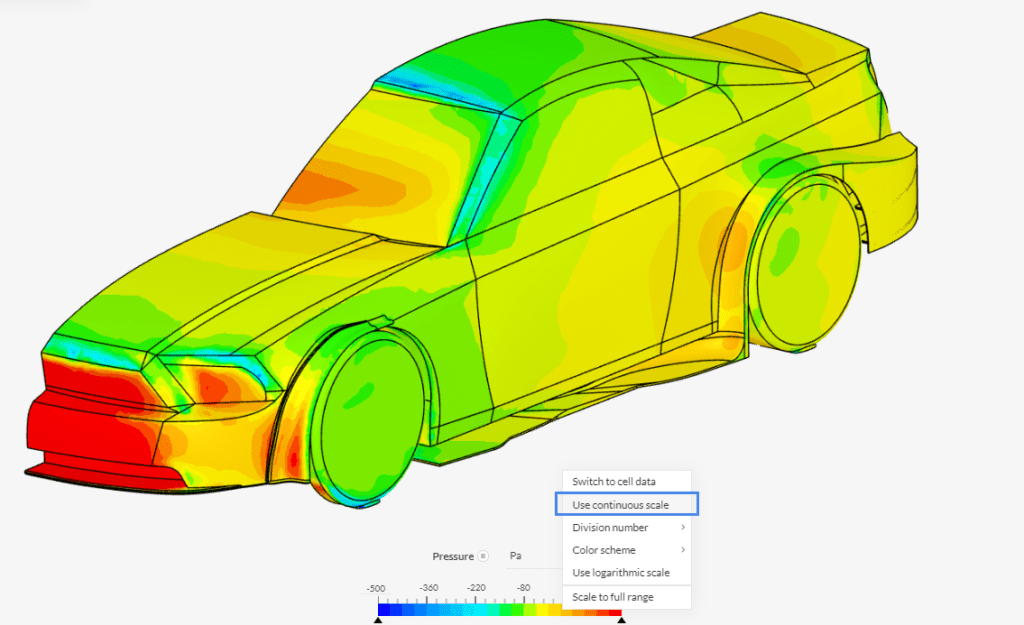

In Figure 52, we have the pressure contours on the car body. As previously discussed, these are gauge pressures. In the areas where aerodynamic flow stagnation occurs (e.g., on the bumper), pressure exhibits larger values. To add a smooth distribution of the colors on the vehicle, right-click on the legend at the bottom, and select ‘Use continuous scale’ :

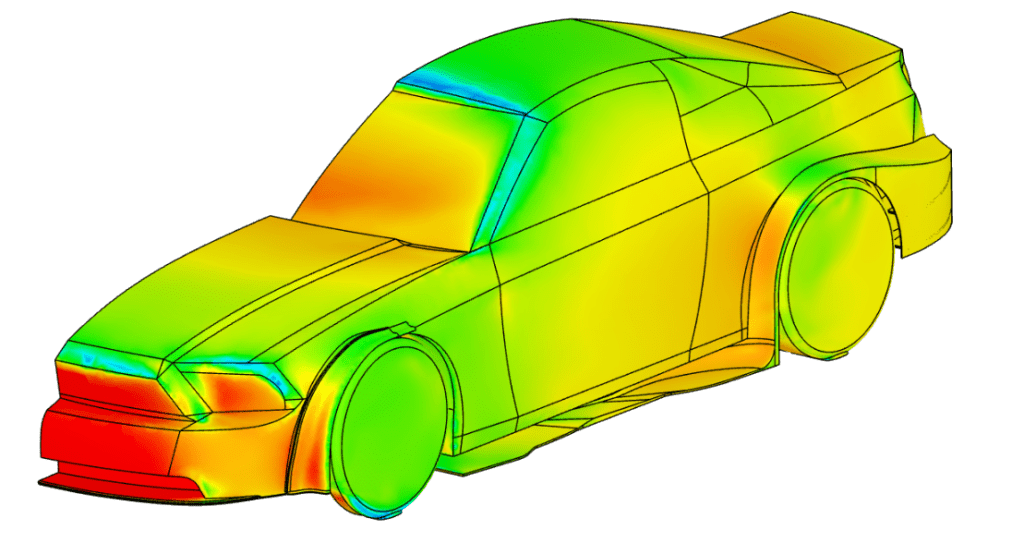

The upgrade in the visualization quality is evident:

If you want to observe the aerodynamic flow characteristics around the car, then you can obtain some insights with a ‘Cutting Plane’:

Configure the cutting plane by following the steps below:

From the figure above, we can see that the car creates a disturbance in the aerodynamic flow which produces high turbulent kinetic energy, especially behind the trunk, closer to the ground.

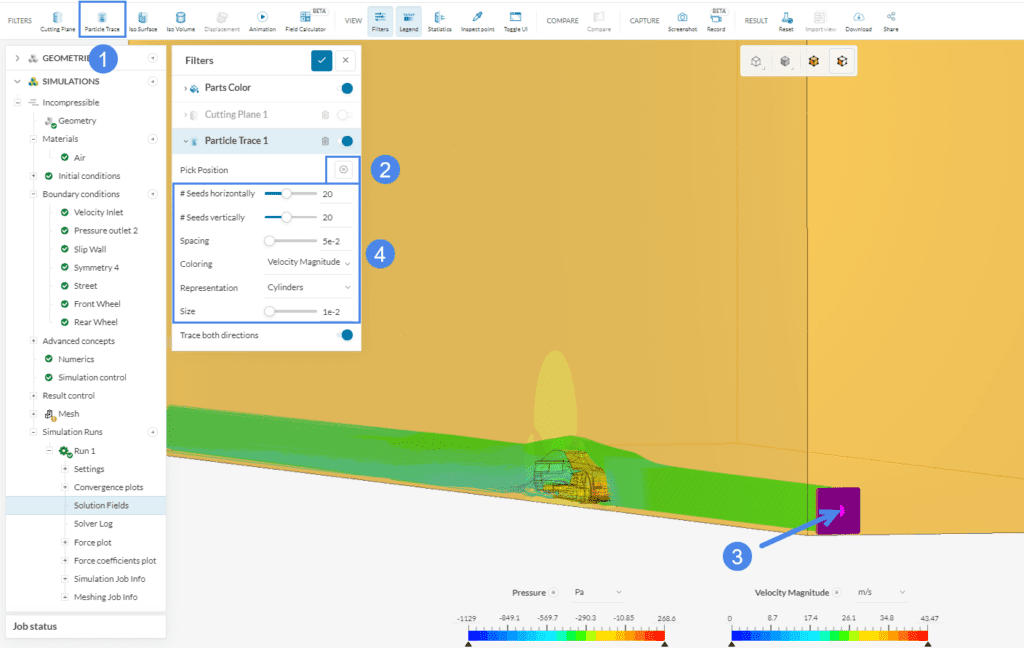

Streamlines are useful to visualize the aerodynamic flow path around the car. To do this, select ‘Particle Trace’ from the Filters panel and its settings will be shown.

Next, pick the start position of the particles by clicking the button beside Position.

Animations can be started by choosing ‘Animation’ from the Filters panel. After changing the Animation type to ‘Particle Trace’, click the play button to start the animation.

The result is shown in the animation below, for better visualization the traces has been changed from cylinders to comets:

When combining the pressure distribution on the surfaces of the car with the velocity streamlines around the car, we can see that high pressure is created at the front when the velocity is at the lowest. Aerodynamic flow seems to be accelerating as it travels over the roof and beyond. A Suction region with very low velocities can be analyzed with blue streamlines.

You can analyze the aerodynamic flow results further with the SimScale post-processor. Have a look at our post-processing guide to learn how to use it.

Congratulations! You finished the aerodynamic flow behavior tutorial!

Note

If you have questions or suggestions, please reach out either via the forum or contact us directly.

Last updated: September 28th, 2023

We appreciate and value your feedback.

Sign up for SimScale

and start simulating now