Documentation

Buoyancy is an upward force exerted by a fluid on an immersed object in a gravity field. In fluids, pressure increases with depth. Hence, when an object is immersed in a fluid, the pressure exerted on its bottom surface is higher than the pressure exerted on its top surface.

This difference in pressure leads to a net upward force (buoyancy force). This force opposes the gravitational force and is equivalent to the weight of the fluid that would otherwise occupy the volume of the object, i.e. the displaced fluid.

Thus, if the object is less dense than the fluid, the buoyancy force will be higher than its weight, and the object will float. On the contrary, if the object is denser than the fluid, it will sink. The static balance occurs when the weight of the immersed part of the object is the same as the weight of the displaced fluid; i.e., the densities coincide.

Note that the density of the object is generally taken as a simple ratio between the mass and volume of the immersed part. The most common case is the immersion of a solid into a liquid (e.g., a ship in the sea), but that’s not all. A rising bubble (gas in liquid), a falling droplet (liquid in gas), and aerostats (warm air into cold air) are examples of phenomena ruled by buoyancy forces, as well.

The physical principle of buoyancy was first described by Archimedes of Syracuse in his work “On Floating Bodies”, written in the 3rd century B.C.. His book is a collection of physical observations and assumptions on the physics of fluids, which led to an a-posteriori definition of the so-called “Archimedes’ principle”.

Archimedes’ principle states that “any object, wholly or partially immersed in a fluid, is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object”.

Hence, centuries before the development of a consistent scientific method, Archimedes pointed out the two main factors which affect the buoyancy forces:

The product of the fluid density and the submerged object’s volume is “the weight of the fluid displaced by the object”.

Buoyancy forces can be found in the static equilibrium of any domain submerged into a fluid. But they become evident when this domain has different characteristics than the surrounding fluid (e.g. different phase or same phase but different density). Thus, the physical basis of buoyancy can be derived from the static equilibrium of a submerged volume as follows:

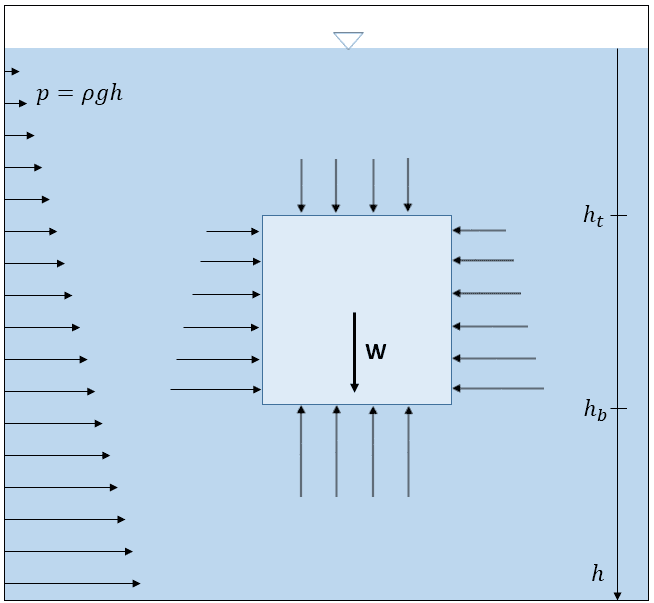

Consider a rectangular volume submerged into a fluid, as shown in Figure 2. Its dimensions are \(L_x\) in the horizontal direction and \(L_y\) in the vertical direction. All the forces exerted on the object can be computed as the integration over the boundary surface of the hydrostatic pressure:

$$ p=\rho g h \tag{1}$$

\(ρ\) is the density of the fluid.

\(g\) is the gravity acceleration.

\(h\) is the depth with respect to the free surface.

The horizontal equilibrium is computed as the sum of the forces exerted on the left face of the rectangle and the forces exerted on the right face:

$$ F_x = \int_{h_b}^{h_t}p\,dh-\int_{h_b}^{h_t}p\,dh = \int_{h_b}^{h_t}\rho g h\,dh-\int_{h_b}^{h_t}\rho g h\,dh \tag{2}$$

All the variables are considered independent of the \(x\) coordinate. Hence, the horizontal equilibrium is naturally achieved (i.e. \(F_x≡ 0\)); thus, we see no buoyancy forces.

The same procedure can be done along the vertical direction:

$$ F_h = F_{buoyancy} – W=-\int_{L_x}p_t \, dx + \int_{L_x}p_b \, dx – W \tag{3}$$

\(L_x\) is the horizontal dimension of the rectangle.

\(W\) is the weight of the object.

\(p_t\) and \(p_b\) are the pressure at the top and the bottom of the rectangle, respectively.

Equation (3) can be developed as:

$$ F_h = -\int_{L_x}\rho g h_t \, dx + \int_{L_x} \rho g h_b \, dx – g\rho_{object}V_{object}$$

$$ =-\rho g h_t L_x + \rho h_b L_x – g \rho_{object}L_x L_y=\rho L_x (h_b-h_t)-L_x L_y g \rho_{object}$$

$$ =\rho g L_x L_y – L_x L_y g \rho_{object}=gL_x L_y (\rho – \rho_{object}) \tag{4}$$

From equation (4), we can deduce all the main features of buoyancy-ruled phenomena:

The procedure for a finite 2D-square object can be extended to a generic infinitesimal volume and be used for any interface shape and fluid mechanics problem. The equilibrium for an infinitesimal part of a continuum is given by the differential equation:

$$ f+div(\sigma)=0 \tag{5}$$

\(f\) is the external body force density.

\(σ\) is the Cauchy stress tensor.

In our case, the only external volumetric force is gravity (weight), thus:

$$ f=\rho g \tag{6}$$

To compute the total buoyancy force, we need to sum up all the surface forces exerted by the fluid on the interface with the immersed volume. These forces can be derived by the stress tensor as:

$$ t^n=n\cdot \sigma \tag{7}$$

\(n\) is the unit-length normal to the surface.

\(t^n\) is the surface force exerted by the fluid on the infinitesimal surface defined by \(n\).

To obtain the total force exerted on a finite-dimensional surface, we have to integrate \(t^n\) over the volume boundaries:

$$ F_{buoyancy}=\int_S t^{n}\, dS = \int_S n \cdot \sigma \, dS \tag{8}$$

By applying the Gauss theorem, the surface integral can be transformed into a volumetric integral:

$$ F_{buoyancy}=\int_V div(\sigma)\, dV \tag{9}$$

Thus, by substituting equations (5) and (6) in equation (9), we obtain the total value of the buoyancy forces:

$$ F_{buoyancy}=-\int_V f\, dV=-\rho g \int_V \, dV \tag{10}$$

\(V\) is the volume of the immersed domain, and the sign “\(-\)” means it is opposed to gravity.

We notice that \(ρ\) and \(g\) are considered uniform in the fluid for sake of simplicity and thus taken out from the integral.

Equation (10) states again the same principles that Archimedes proposed and that had been obtained in the didactic case in equation (4).

It is important to note that buoyancy is not always enough to analyze the static or dynamic balance of a volume immersed in a fluid, and other variables could be considered to have an accurate prediction of the flow.

For instance, surface tension is an additional force applied to the fluid-object interface, which affects both the dynamics (e.g. sinking object) and the statics (e.g. sunk object) of the problem. The dynamics of buoyancy are also highly affected by the viscosity of the fluid and the turbulence of the flow.

Also, the main quantities may not be constant in time and uniform in space. The following may change:

For all these reasons, buoyancy forces are usually considered as only a part of the fluid dynamics problem, described by the Navier-Stokes equations. In the Navier-Stokes equations, buoyancy is naturally considered through the non-uniformity of density in the fluid domain.

However, the implementation of this case is not usually straightforward. Hence, in many cases, the buoyancy force is modeled as an external volumetric force, while the density is considered constant for the inertial computations. This approximation is referred to as the “Boussinesq approximation”. It is commonly used to model natural convection phenomena in which the density variation is due to temperature evolution.

As stated before, buoyancy should not be referred only to solid-in-liquid cases (e.g., ships in water). At least two major application categories can be directly linked to buoyancy effects: natural convection and multiphase flows.

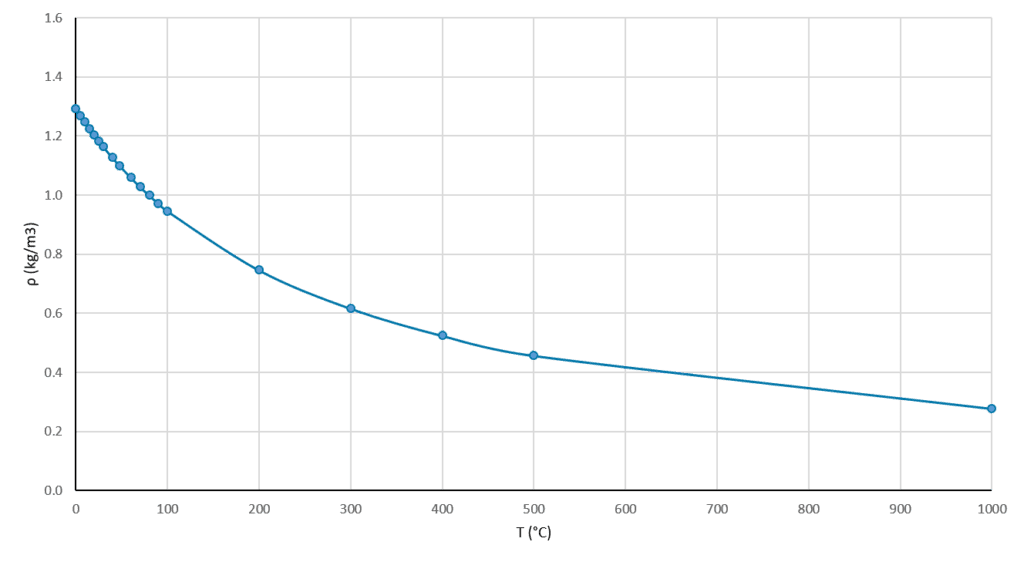

Natural convection is based on the fact that materials become less dense with an increase in temperature (see Figure 3).

This means that a warm fluid will “float” when immersed in a region of the same fluid but colder. In this case, we will not speak of “floating” or “sinking” but of upward streams of hot fluid and downward streams of cold fluid. This phenomenon is usually coupled with thermal analyses, and it is the base of many applications such as meteorology, steel casting, and house heating/cooling.

Natural convection is often enhanced by a forced flow imposition to obtain certain conditions. In this case, we speak of “forced convection”, in which buoyancy forces are still present but less dominant. Figure 4 shows the natural convection induced by air conditioning in a theater space. The AC blows in cold air at the top of the space, which streams down due to the upward buoyancy forces of the warm air at the bottom of the space. Thus, the cold air forms downward streams, and the recirculation pattern is shown in the figure below.

Unlike natural convection, the variation of density in multiphase flows is not due to a difference in temperature but to a difference in the state of matter. If we limit ourselves to fluid mechanics, the two most common possibilities are liquid-in-gas and gas-in-liquid. In both cases, the phase with higher density will tend to move downward.

Figure 5 shows the case of a rising bubble. Since the gas bubble is lighter than the surrounding liquid, the buoyancy forces are stronger than its weight. These unbalanced forces turn into inertial forces, leading to the dynamic response of the bubble.

Note that the bubble is not only translating but also deforming. This is due to the fact that buoyancy is not the only force acting on the bubble – surface tension and viscosity forces also affect the flow.

With SimScale, you can simulate and visualize effects that are influenced by buoyancy. Using computational fluid dynamics (CFD), you can view fluid flows and identify the buoyancy effect.

An example is the simulation below, where you can see the heat emitted from a radiator in a room. The warm air goes straight up the wall until it hits the ceiling and therefore gets distributed in the apartment.

Interested in simulating? Try it for yourself by signing up, and begin simulating right here in your browser.

Sign up!

Create a SimScale account and perform a buoyancy simulation today.

Last updated: August 11th, 2023

We appreciate and value your feedback.

What's Next

What is Aerodynamics?Sign up for SimScale

and start simulating now