Documentation

This article provides a step-by-step tutorial for the nonlinear structural analysis of a wheel. The objective of this simulation is to analyze the deformation and stress distribution across the wheel in operation mode, taking into account the nonlinear phenomena such as hyperelastic material, physical contact, and alternating load.

This tutorial teaches how to:

The typical SimScale workflow will be followed:

To start, you can import a copy of the project into your workbench by following along the steps by clicking the button below:

The image below illustrates the view after importing the tutorial project. The geometry Wheel appears in the simulation tree, and its corresponding 3D model is displayed in the Workbench. The model can be explored interactively—rotate, zoom, and pan using standard CAD navigation controls.

This simulation takes advantage of the model’s double symmetry for two main purposes:

Utilizing symmetry whenever possible is recommended, as it leads to faster and more stable simulations without compromising accuracy.

The ‘Edit a Copy’ option in the geometry pop‑up (Figure 3) launches the CAD Edit environment. Within this workspace, the ‘Split’ operation isolates the symmetrical portion of the model, removing redundant geometry and retaining only the region required for the simulation.

This operation extracts one half of the model.

To obtain the quarter symmetry, repeat the ‘Split’ operation:

The resulting geometry should resemble the one shown below, representing one-quarter of the original model aligned with both symmetry planes. This reduced model retains the essential structural behavior while significantly decreasing computational effort.

Finally, click ‘Save’ in the top-right corner to apply the changes and import the modified geometry into the Workbench for simulation.

The newly created geometry will appear as ‘Copy of Wheel’ by default. Rename it to something more descriptive, such as ‘Wheel–Quarter’, for easier identification during the simulation setup.

Now the simulation setup can be started. Follow these steps to create a new simulation:

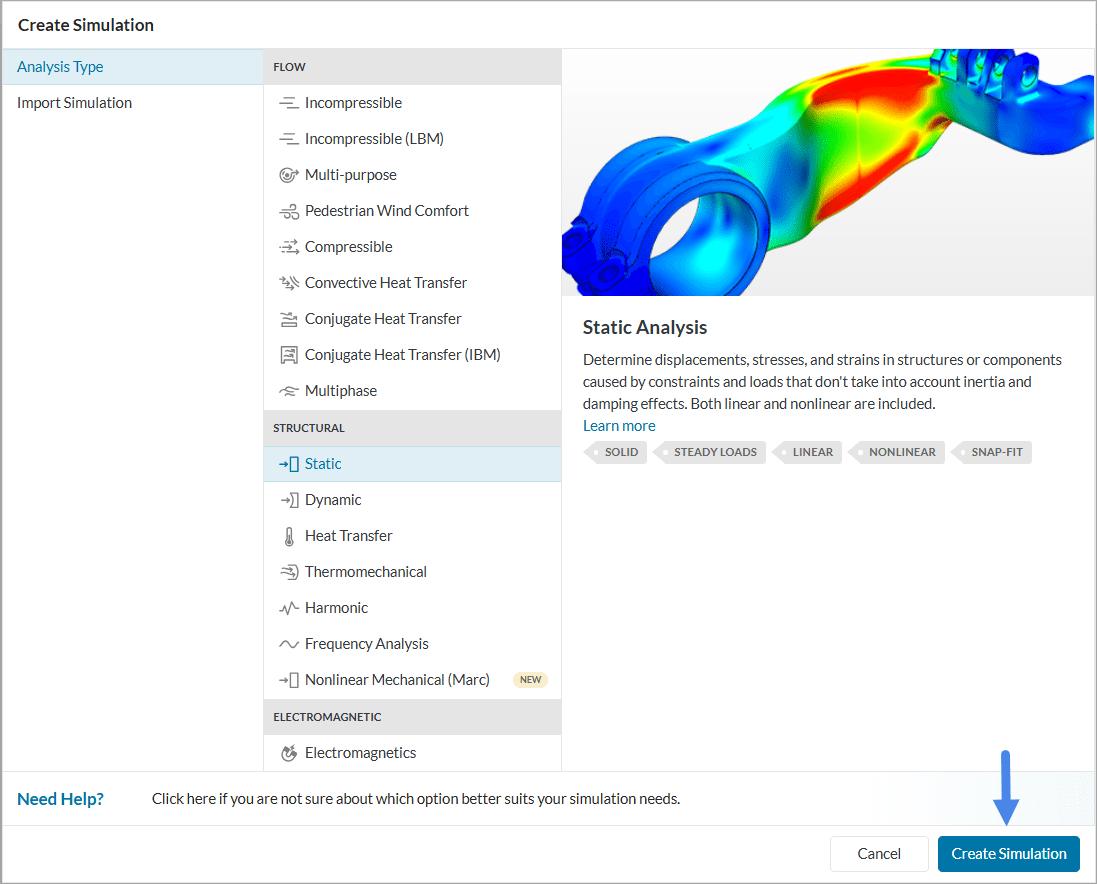

The simulation library window appears. Select the ‘Static’ analysis type and click the blue ‘Create Simulation’ button at the bottom:

A new simulation tree is then automatically generated in the left panel, containing all the parameters and settings required to fully define the analysis. Each item in the tree is marked with a status indicator: a green check signifies that the item is complete, a red circle indicates a required input that is still missing, and a blue circle denotes an optional setting. These visual cues help guide the simulation setup process. Refer to the figure below for an illustration.

Since this structural simulation involves nonlinearities—such as physical contact, hyperelastic material behavior, and varying loads—the nonlinear analysis option must be enabled. In the ‘Global settings’ panel that appears after creating the simulation, activate the ‘Nonlinear analysis’ toggle to account for these effects in the solver.

You can find more details about what characterizes a static analysis here.

The analysis of the wheel will include the following operating conditions:

In this simulation, the wheel rim is modeled using polypropylene, a common thermoplastic material. The wheel tire is defined as rubber, a hyperelastic material expected to undergo large deformations under load.

The loading conditions include:

To realistically capture the interaction between the tire and the ground, the model must include physical contact between these two components.

The figure below summarizes the key nonlinear modeling conditions applied in this analysis.

Two contact conditions are defined in this simulation:

The bonded contact between the rim and tire is automatically detected and created by SimScale. It appears under the ‘Contacts’ section in the simulation tree as Bonded 1.

Next, create a Physical contact definition to define the interaction between the tire and the ground. Follow the steps illustrated in the accompanying image to assign the correct surfaces and parameters. This contact setup enables the solver to accurately model the nonlinear deformation and contact response under load.

Click the check mark ![]() to finish the setup.

to finish the setup.

The selection of faces to be assigned the master/slave is performed according to the key concepts explained in the following article.

To define the material behavior, add the required material models from the material library. Begin by clicking the ‘+’ button next to the Materials node in the simulation tree. This opens the materials library, where the appropriate material can be selected. After selecting the desired material, click ‘Apply’ to load its standard properties into the simulation setup.

In the settings panel, the target body that will have the material properties applied is assigned. Accept the selection with the blue checkmark ![]() .

.

Use these instructions to assign the following material to each body in the CAD model:

For the ground body, select Concrete from the material library. Assign it to the Ground geometry by selecting the corresponding body either directly in the viewer or from the Scene tree on the right panel, as illustrated in the figure below.

For the wheel rim, select the PP (polypropylene) material from the material library, and assign the Rim body.

For the wheel tire, select Rubber from the material library and assign it to the Mount and Tire bodies. Due to the softness of this component and the expected large deformations from loading and contact with the ground, a hyperelastic material model is required.

To configure this:

This setup ensures accurate representation of the nonlinear elastic response of the rubber material.

The input values are:

To define the boundary conditions, click the ‘+’ button next to the ‘Boundary conditions’ node in the simulation tree. From the drop-down menu, select the appropriate boundary condition type for the simulation setup, as shown in Figure 19. This step allows the specification of constraints and loads necessary for the analysis.

The first boundary condition fixes the ground in place. To define it, select ‘Fixed support’ from the boundary conditions drop-down menu. Then, activate ‘Assign Volume’ from the top toolbar (Figure 20) and select the ground body either in the viewer or from the scene tree. This constraint ensures that the ground remains stationary throughout the simulation.

The second boundary condition restricts normal displacement along the symmetry plane used to cut the model. Select the ‘Symmetry plane’ boundary condition from the list and assign all faces that lie on the symmetry plane, as illustrated in the accompanying image. This constraint ensures that the model behaves as if the full geometry were present.

Use the same procedure as before to define the second symmetry plane, this time aligned with the ‘Z’ direction. Select the corresponding faces and assign the ‘Symmetry plane’ boundary condition. The process is illustrated in the figure below.

Why Is the Symmetry Not Applied to the Ground?

A Symmetry boundary condition constrains displacement normal to the selected face, while allowing movement in the tangential directions. In this simulation, a Fixed support is applied to the entire Ground volume, constraining movement in all three directions. As a result, the ground behaves as a rigid body, and applying an additional symmetry condition to its faces is unnecessary.

To apply the operating load supported by the wheel, select a ‘Force’ boundary condition from the drop-down menu. Click the table icon to define a time-dependent load profile, as illustrated in the accompanying image. Assign it to the central cylindrical faces, as shown in Figure 23.

The Specify value window will appear, allowing input of the load curve. In this case, use the Table input option and configure it as shown in the image below. To visualize the loading profile, change the Column for Y axis to ‘f<y>’. This will generate a graphical representation of the applied force over time.

| t \([s]\) | Fx \([N]\) | Fy \([N]\) | Fz \([N]\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 0 | -1000 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 0 | -500 | 0 |

Notice that the load force starts at zero, maxes out at \(t = 0.5\ s\) and then goes back down to the mean value at \(t = 1.0\ s\). The negative value indicates the force direction with respect to the Y axis.

Did you know?

This type of load curve allows us to study the history of the deformations, and the amplitude of the operating stresses, which are useful in fatigue analysis and other failure assesments.

Time in nonlinear static analysis

As this is a pseudo-static simulation, the time units are expressed in seconds, but actually do not have physical meaning. It just indicates the sequence of the events. There are no velocity or acceleration effects taken into account in the model, and all phenomena are assumed to happen slowly.

The Numerics section of the simulation tree can remain unchanged. The default values are well-calibrated and sufficient for solving this case effectively. In most simulations, modifications to these parameters are unnecessary due to the carefully tuned defaults.

Similarly, no changes are required in the Simulation Control section. Since the simulation interval is assumed to be the default range of 0 to 1, this section can be left as is.

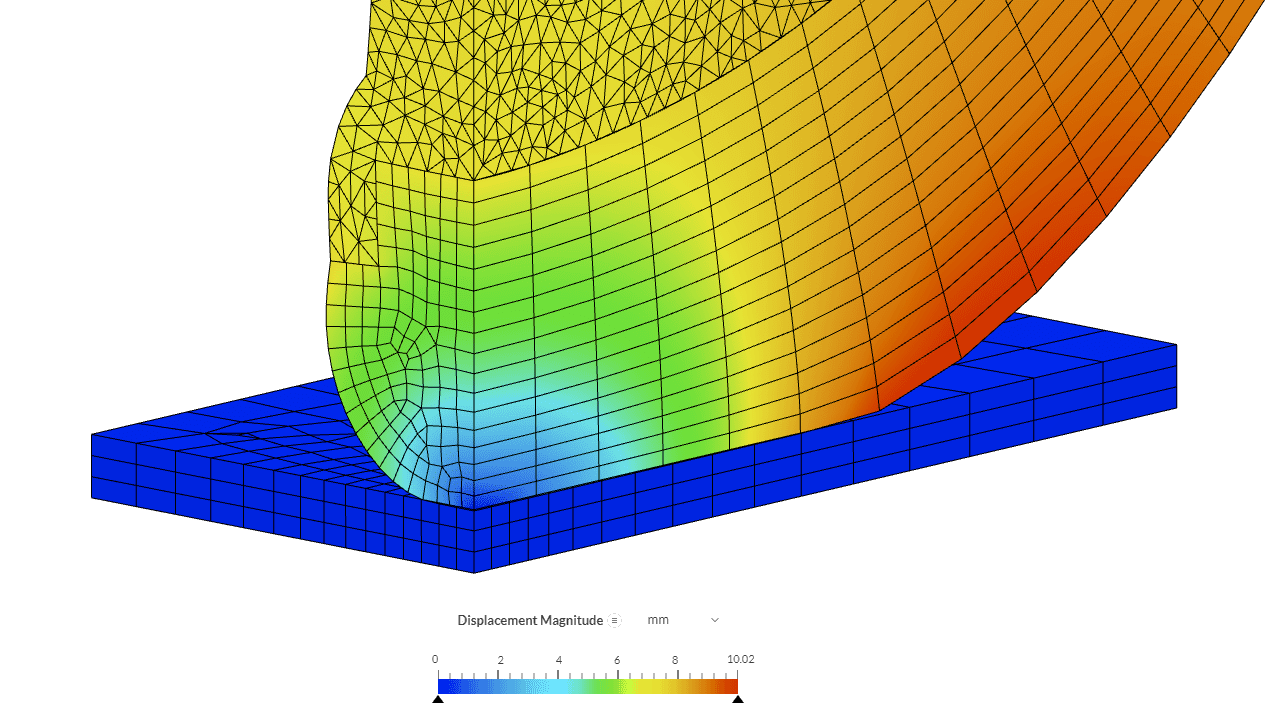

To achieve optimal results, a structured mesh will be created using the Standard meshing algorithm. Open the Mesh section in the simulation tree and review the default settings, which will remain unchanged. Note that it is not necessary to click ‘Generate’ at this point, as the mesh will be computed automatically during the simulation run.

To define mesh refinements and build a structured mesh, click the ‘+’ button next to Refinements under the Mesh node. Then, select the desired refinement type from the available options.

For the first refinement, create an Extrusion mesh refinement. This refinement type enables the generation of structured meshes composed of hexahedral or prismatic elements, which typically offer better numerical performance and accuracy compared to unstructured tetrahedral meshes.

To ensure a valid sweep, select opposite faces that are connected one-to-one at their vertices, as illustrated in the accompanying figure. This ensures proper extrusion and structured element generation across the selected region.

The prismatic shape of the tire allows for structured meshing through extrusion. Create a second Extrusion mesh refinement and configure it as shown in the figure. This approach ensures a high-quality mesh for the tire region, improving accuracy in areas expected to undergo large deformations.

Finally, since the rim has a more complex geometry that requires an unstructured mesh, apply a Volume custom sizing refinement to control the mesh quality. This refinement limits the element edge length, helping to maintain an optimal aspect ratio and overall mesh resolution.

Create the refinement under Refinements > Volume custom sizing, and configure it according to the parameters shown in the figure.

The final step before launching the simulation is to create a run. To do this, click the ‘+’ button next to Simulation Runs in the simulation tree.

In the pop-up window that appears, enter a descriptive name for the run, then click ‘Start’ to begin the computation.

The Job status item below the simulation tree updates the status of the run. Also, a Solver log is provided after a few seconds, which shows the advancements of the actual computing algorithm. The simulation run should take a few minutes to be carried out. Once the simulation run is Finished, we can post-process the results.

Once the simulation is complete, the wheel load results can be post-processed on the platform using one of the following methods:

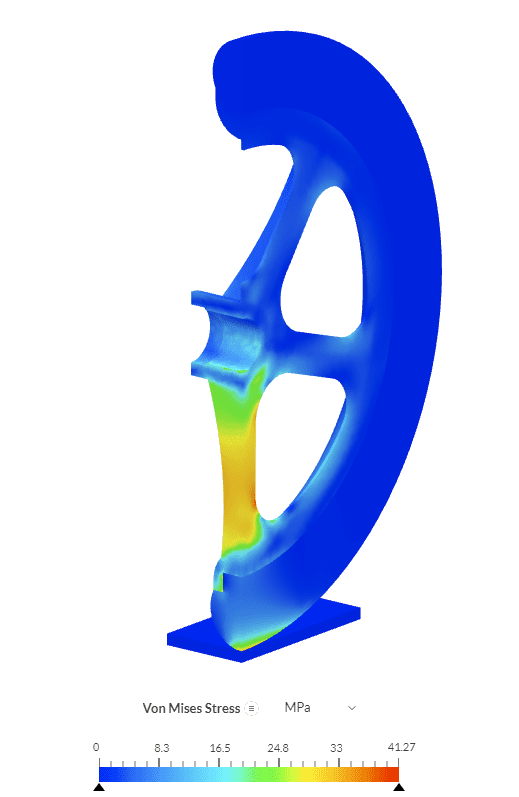

In order to examine the stress results on the wheel, we should select the field assigned to the Parts Color as ‘Von Mises Stress’:

The parts are now colored according to the levels of stress, but we will perform some tweaking to better visualize the results:

You should end up with the following visualization:

Figure 33 shows the stress distribution on the model of the wheel at the time of maximum load. It can be seen that maximum stress levels of around 41.3 \(MPa\) occur at the rim radius element and at the contact patch between the tire and the ground.

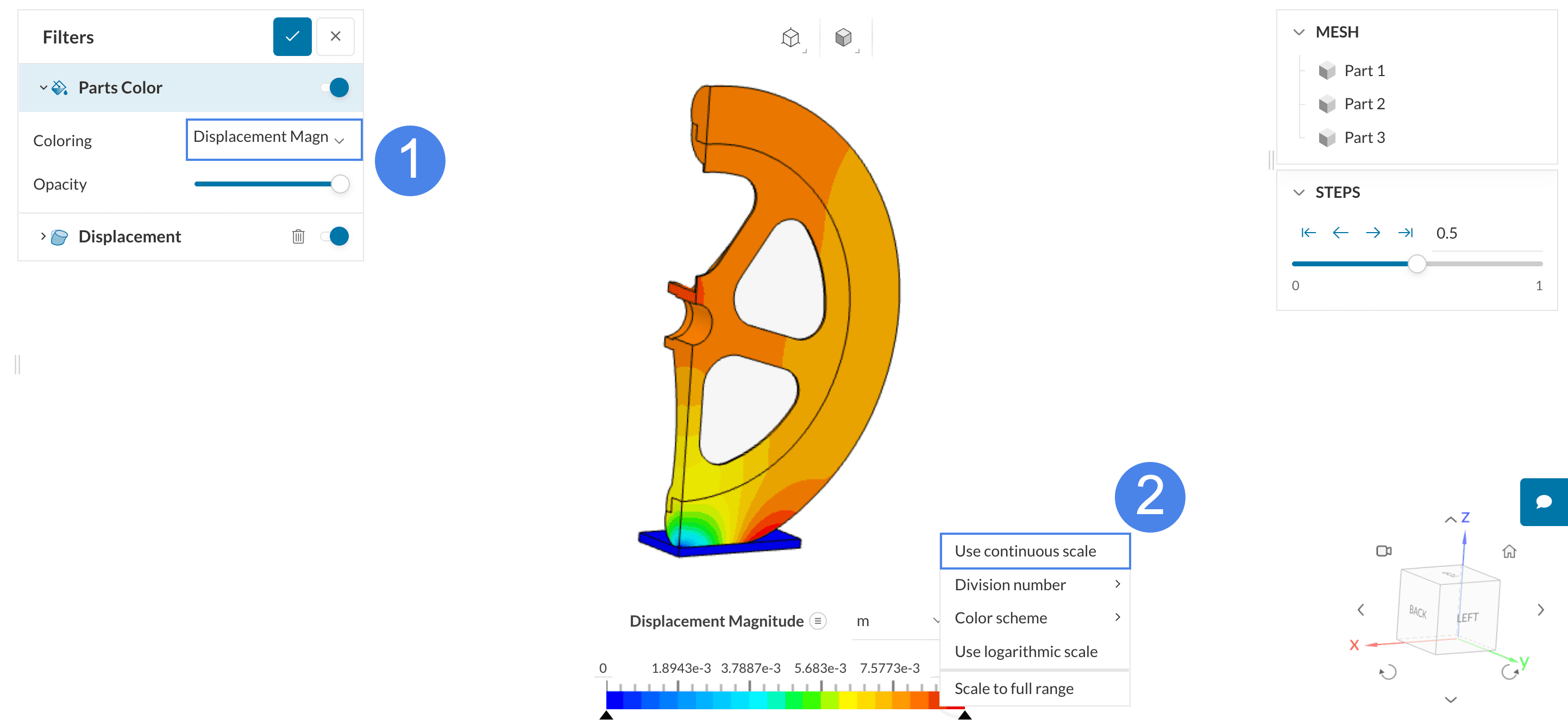

In order to visualize the deformed shape of the wheel, create a Displacement plot:

The deformed shape along with the coloring can then be inspected:

The details of the deformation of the tire in the region of contact with the ground are well appreciated.

We can visualize the loading and unloading process and the evolution of the deformation by creating an Animation filter, the same way we added the Displacement filter (see Figure 34):

The default parameters are enough for our purpose. Click the ‘Play’ button to start the animation and you should see something as shown:

Animation 1 shows the deformation process and the corresponding contour plot for the von Mises stress. The effect of the load curve and the points of maximum deformation and stress can be appreciated.

Finally, we can take a look at the load vs. deformation plot, created locally by measuring the displacement of a point at the center of the wheel in post-processing tool Paraview, and using the known force curve:

Figure 38 shows the vertical displacement magnitude of a point at the load application face, versus the applied load magnitude. Here, the nonlinear behavior of the model can be clearly seen, with the curvature of the load vs displacement curve following the hyperelastic behavior on the loading and unloading steps.

If you want to learn more about SimScale’s online post-processor, you can have a look at our dedicated guide:

Congratulations, you finished the differential casing tutorial!

Note

If you have questions or suggestions, please reach out either via the forum or contact us directly.

Last updated: July 23rd, 2025

We appreciate and value your feedback.

Sign up for SimScale

and start simulating now