Without effective thermal management, sensitive electronic components face a swift and devastating impact on performance, reliability, and lifespan, particularly when considering their cooling requirements.

As power densities increase and form factors shrink, the choice between a passive or active cooling strategy becomes one of the most critical decisions in the design cycle. Making the wrong call leads to costly redesigns and field failures.

This is where simulation provides a decisive advantage. Cloud-based analysis allows engineers to test, validate, and optimize thermal solutions before committing to physical prototypes, transforming a high-stakes gamble into a predictable science. This article will dissect the two primary cooling methodologies – passive and active cooling methods – and provide a comprehensive framework for selecting and simulating the optimal approach to provide cooling for your project.

Passive Cooling: The Silent Guardian

Passive cooling represents engineering elegance – achieving thermal management without active cooling components consuming additional energy. It is a reliable, silent, and cost-effective solution for dissipating low-to-moderate heat loads, making it a cornerstone of modern electronics design.

What is Passive Cooling?

Passive cooling leverages the fundamental laws of physics to transport thermal energy. It relies on conduction, natural convection, and radiation to move heat from a source to the surrounding environment. Because these systems have no moving parts, the cooling systems are inherently fail-proof from a mechanical standpoint. This is a key principle behind passive cooling strategies offering unparalleled long-term reliability.

The process begins with conduction, governed by Fourier’s Law (q=−k∇T), where heat moves through a solid material like aluminum or copper. The heat then transfers to the surroundings via natural convection and radiation. Radiative cooling, described by the Stefan-Boltzmann Law (P=ϵσA(Thot4−Tcold4)), is why heat sinks are often anodized or painted black—to increase their emissivity (ϵ) and maximize heat dissipation.

How Does Passive Cooling Work?

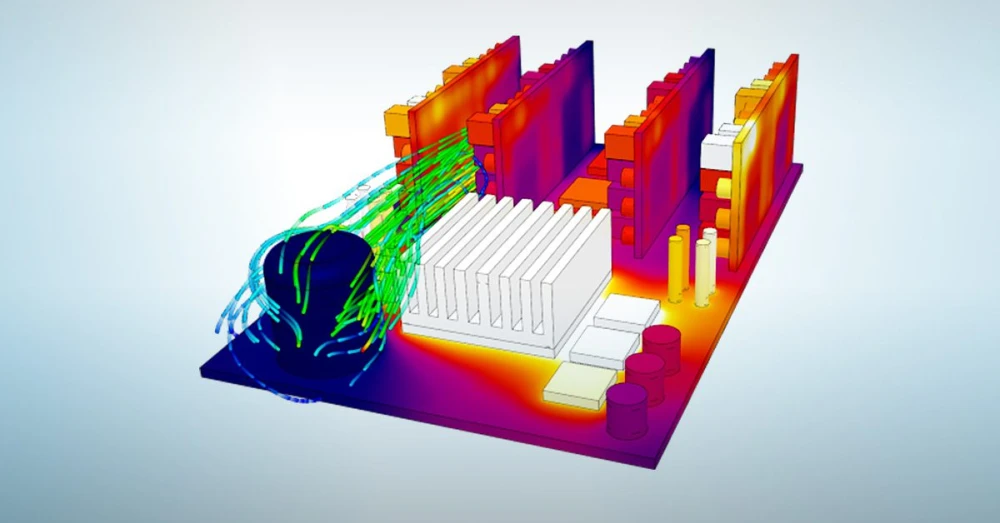

The primary workhorse of passive cooling is the heat sink, which uses a large surface area to efficiently transfer heat. The process is straightforward:

- Conduction: Heat is generated by the electronic component and conducted into the heat sink base, often through a Thermal Interface Material (TIM) that minimizes thermal resistance on the interface.

- Dissipation: The heat spreads through the heat sink to its fins, which dramatically increase the surface area for dissipation into the ambient via natural convection and radiation.

More advanced passive systems like heat pipes and vapor chambers use two-phase heat transfer. A sealed working fluid evaporates at the hot interface (absorbing latent heat) and condenses at the cold interface (releasing heat), achieving an effective thermal conductivity that is orders of magnitude higher than solid copper.

Benefits of Passive Cooling

- Extreme Reliability: With no moving parts, there are zero mechanical failure points, which is essential for systems in inaccessible locations like satellites or remote telecom towers. Systems without openings offer a huge advantage in terms of preventing dirt and dust to negatively affect the cooling system or require regular maintenance.

- Zero Operational Cost: These solutions add nothing to a product’s energy consumption or a facility’s utility bill.

- Silent Operation: The absence of fans is a critical requirement for noise-sensitive applications like high-fidelity audio equipment or medical devices.

- Lower Cost: Passive solutions are typically cheaper to manufacture than their active counterparts.

Passive Cooling Systems Examples

- Extruded Aluminum Heat Sinks: The most common type, found in routers, set-top boxes, and solid-state drives (SSDs).

- Heat Pipes & Vapor Chambers: Used in high-performance laptops and compact, fanless PCs.

- Strategically Vented Enclosures: Designing a product’s housing to maximize the natural “chimney effect” of rising hot air.

- Phase Change Materials (PCMs): Materials that absorb thermal spikes by melting and re-solidify when the load decreases.

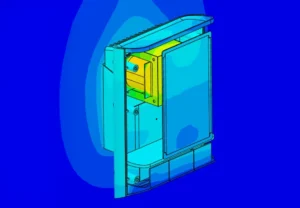

Real world passive cooling example

Cobalt Design used SimScale to reduce their passive heat sink temperature by 11% through the analysis of existing designs which highlighted localized peak temperatures inside the unit without an adequate exfiltration path.

Active Cooling: The Power Play

When the heat load generated by a system surpasses the capacity of passive methods, engineers must turn to active cooling. This approach uses forced convection components to dramatically accelerate heat removal, making active cooling solutions essential for enabling performance levels that would be otherwise impossible.

What is Active Cooling?

Active cooling is any thermal management system that consumes energy to enhance heat transfer. By introducing a mechanical component like a fan or pump, these systems overcome the limitations of natural convection, allowing them to manage much higher heat fluxes within a compact form factor.

How Does Active Cooling Work?

The most common form of active cooling is forced convection. A fan or blower moves air across a heat sink at high velocity. This turbulent flow dramatically increases the heat transfer coefficient (h), enhancing the cooling performance and meaning more thermal energy is transferred away from the component.

For more demanding applications, active liquid cooling is used. A pump circulates a coolant through a cold plate mounted on the heat source. The heated liquid then flows to a radiator, where a fan dissipates the heat into the air, improving overall energy efficiency. A case study on high-power electronics demonstrated that a direct liquid cooling solution could maintain a component’s temperature at 55°C, while an air-cooled solution could only manage 77°C under the same heat load—a crucial 22°C difference.

Benefits of Active Cooling

- Superior Thermal Performance: The ability to dissipate immense heat loads enables high-performance CPUs and GPUs to operate at peak potential without throttling.

- Precise Thermal Control: Fan speeds can be dynamically adjusted using Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) based on sensor data, optimizing cooling while minimizing noise and power use.

- Design Compactness: Active cooling achieves high performance in tight spaces, like blade servers, where a comparable passive solution would be too large.

Active Cooling Systems Examples

- Axial Fans & Centrifugal Blowers: Found in virtually all desktop computers, servers, and industrial cabinets.

- Closed-Loop Liquid Coolers: Standard for enthusiast PCs, workstations, and increasingly, direct-to-chip data center cooling.

- Thermoelectric Coolers (TECs): Solid-state Peltier devices that “pump” heat electrically, used for spot cooling in lab equipment and portable refrigerators.

Real world active cooling example

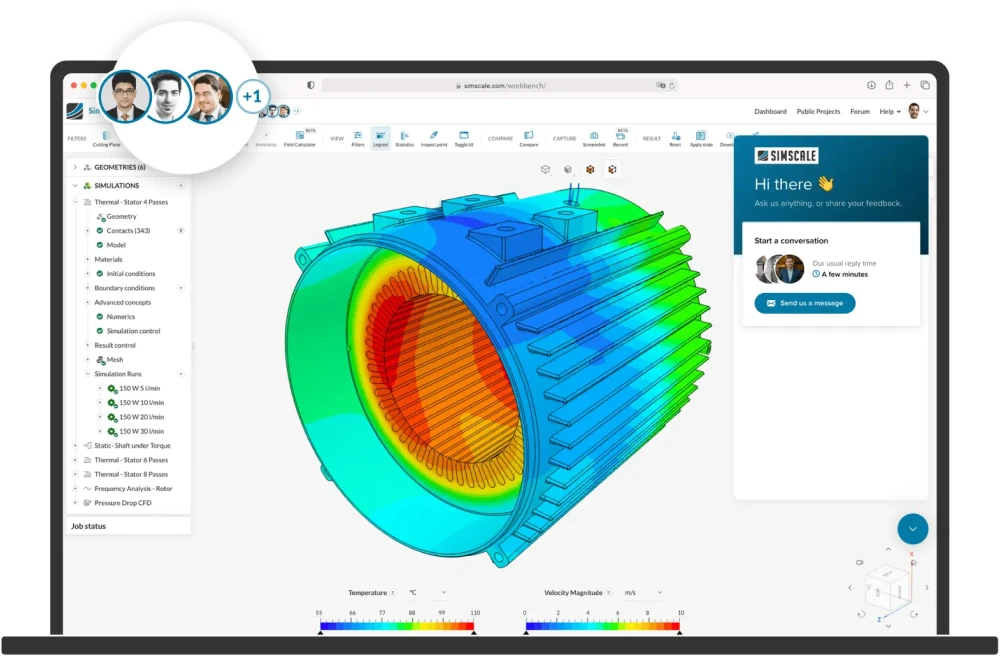

Rimac Automobili used SimScale to improve the thermal management of their EV batteries which lead to a 96% time saving for simulations as well as improved overall performance.

Choosing Active vs. Passive Cooling: A Design Framework

The decision between active and passive cooling is a trade-off analysis based on key design constraints. There is no single “best” solution, only the most appropriate one.

- Thermal Design Power (TDP) & Heat Flux: This is the starting point. Below ~15W, passive solutions usually suffice. Above 100W, active cooling is almost always necessary. The region between is a complex trade-off zone.

- Environment & Form Factor: High ambient temperatures reduce the effectiveness of all cooling but can render passive solutions inadequate. The available volume will also dictate if a large passive heat sink is even a viable option.

- Acoustics & Vibration: If silent operation is a primary requirement (e.g., medical devices), passive cooling is the clear choice. Fans introduce noise and micro-vibrations that can be problematic for sensitive equipment.

- Reliability & Maintenance (MTBF): Compare the Mean Time Between Failures of a fan (30k-70k hours) against the near-infinite lifespan of a solid heat sink. For products designed to last a decade, a fan is a potential point of failure.

- Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): An active solution has ongoing operational costs due to its power consumption. A slightly more expensive passive solution may have a lower TCO over the product’s lifetime.

Often, a hybrid approach is optimal, using a passive heat sink for normal operation and a fan that activates only under peak thermal load.

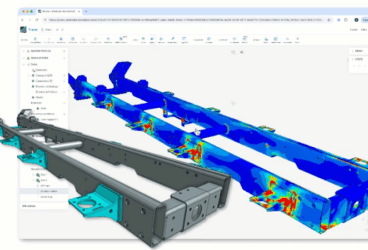

Simulate Your Active and Passive Cooling Solution with SimScale

Guesswork and over-engineering are not effective design strategies, especially when it comes to implementing hybrid cooling systems . Before committing to expensive tooling, you must validate your design. Cloud-native simulation with SimScale provides the quantitative proof needed to make data-driven decisions.

- De-Risk Your Design: Identify thermal failures in the digital domain to save weeks of time and thousands in wasted prototypes. Integrating CFD simulation early can reduce the number of physical prototypes required to one or a few at max and transform the physical testing into a pure validation step at the end of the design phase.

- Optimize for Performance: Run parametric studies on heat sink fin geometry or fan placement in parallel on the cloud. This allows you to find the configuration that offers the lowest thermal resistance (Rth) for the lowest mass.

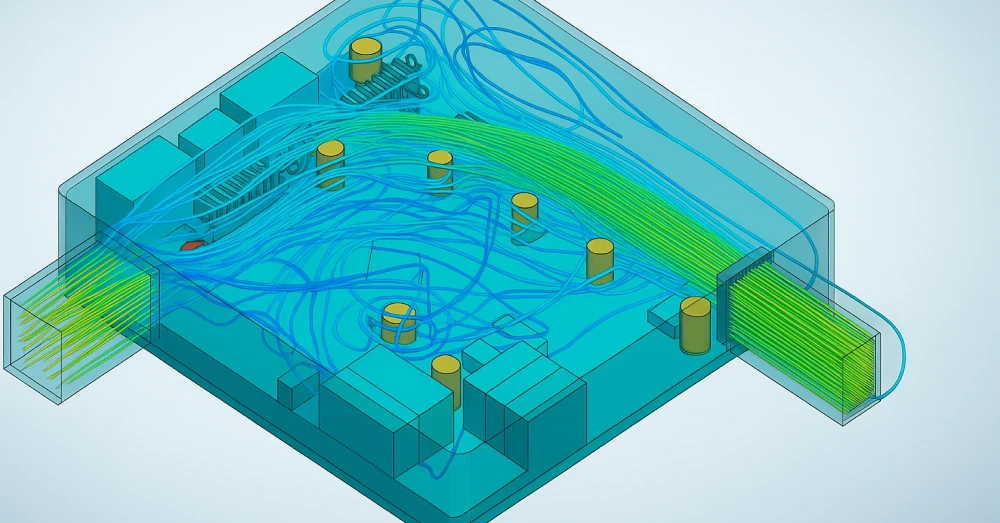

- Visualize the Invisible: Use CFD analysis to get a complete picture of airflow and heat distribution. You can visualize recirculation zones, identify thermal bottlenecks, and ensure your cooling solution performs as intended.

- Quantify with Precision: Move from estimation to prediction. A SimScale thermal simulation provides precise temperature calculations, confirming that a critical processor will be cooled from a dangerous 95°C to a safe 78°C, ensuring you meet reliability targets before manufacturing begins.

Stop gambling with your product’s thermal performance. Start your free trial of SimScale today and discover how cloud-based simulation can help you build more reliable, efficient, and powerful products with confidence.